Event-driven applications are inherently distributed and loosely-coupled. That potentially leads to having many self-contained components in your architecture, managed by multiple teams.

The information exchanged between them must be documented and maintained consistently for everyone’s visibility. AsyncAPI specification steps in to solve that gap.

This post explains how to map a simple event-driven application architecture into corresponding AsyncAPI specifications by walking you through an example.

The event-driven use case

Imagine you are designing a solution to the following use case.

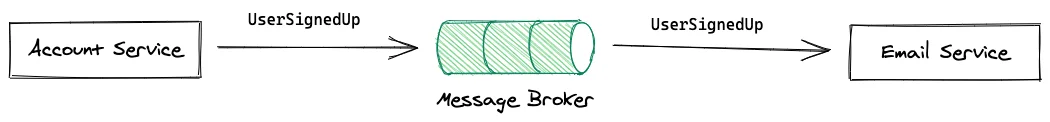

Two event-driven microservices are communicating through a message broker in a publish/subscribe manner. The first service, the Account service, publishes the UserSignedUp event when a new user account is created. The second service, the Email service, subscribed to receive those events to send the new user a welcome email.

We can come up with a simple solution architecture as follows.

The problem

Now we have a solution architecture in place. Should we go ahead and start building?

No! Not so fast. There are strong reasons behind not doing so.

Account and Email services are loosely coupled distributed services, potentially built, operated, and maintained by separated teams. Two services will have their own context boundaries defined. All teams must explicitly define any information exchanged across these boundaries. For example, all teams must maintain broker configurations, topics, and event formats in a central place. Otherwise, maintaining the solution will become a nightmare in the long run.

In our solution, the format of the UserSignedUp event must be consistent across two services. If one team makes a change, it has to be visible across the board.

Therefore, a proper process must be in place to describe different components of an event-driven system and their interactions. AsyncAPI specification comes into play at this point.

AsyncAPI specification to the rescue

AsyncAPI is an open-source initiative that provides both a specification to describe and document your asynchronous applications in a machine-readable format and tooling (such as code generators) to make life easier for developers tasked with implementing them.

AsyncAPI is built on the foundation of OpenAPI specification. A brings in critical activities from the REST API world, from documentation to code generation, from discovery to event management. Most of the processes you apply to your REST APIs nowadays would apply to event-driven/asynchronous APIs.

Currently, the specification is at version 2.0.0.

Documenting the solution architecture

Let’s try to document our solution as per the AsyncAPI specification. Our end goal is to share it with respective teams to generate the implementations, validators, and most importantly, the documentation.

An AsyncAPI document is a file that defines and annotates the different components of a specific Event-Driven Application. The file format must be JSON or YAML; however, only the subset of YAML that matches the JSON capabilities is allowed.

First, we need to identify Applications in the solution.

Identify event-driven applications in the solution

The first step of documenting an event-driven architecture is to identify discrete components that produce or consume events. In AsyncAPI terms, they are commonly referred to as Applications.

As per the specification:

An application is any kind of computer program or a group of them. It MUST be a producer, a consumer or both. An application MAY be a microservice, IoT device (sensor), mainframe process, etc. An application MAY be written in any number of different programming languages as long as they support the selected protocol. An application MUST also use a protocol supported by the server in order to connect and exchange messages.

In our solution, both Account service and Email service can be considered as applications as they produce and consume UserSignedUp events, respectively. Hence, both services will get their own AsyncAPI specification file.

Let’s start with the Account service first.

Documenting the Account service

Create a file called account-service.yaml and add the following content to it.

1asyncapi: 2.0.0

2info:

3 title: Account Service

4 version: '1.0.0'

5 description: |

6 Manages user accounts in the system.

7 license:

8 name: Apache 2.0

9 url: https://www.apache.org/licenses/LICENSE-2.0The first line of the specification starts with the document type, asyncapi, and the version (2.0.0). This line doesn’t have to be the first one, but it’s a recommended practice.

The info object contains the minimum required information about the application. It contains the title, which is a memorable name for the API, and the version. While it’s not mandatory, it is strongly recommended to change the version whenever you make changes to the API.

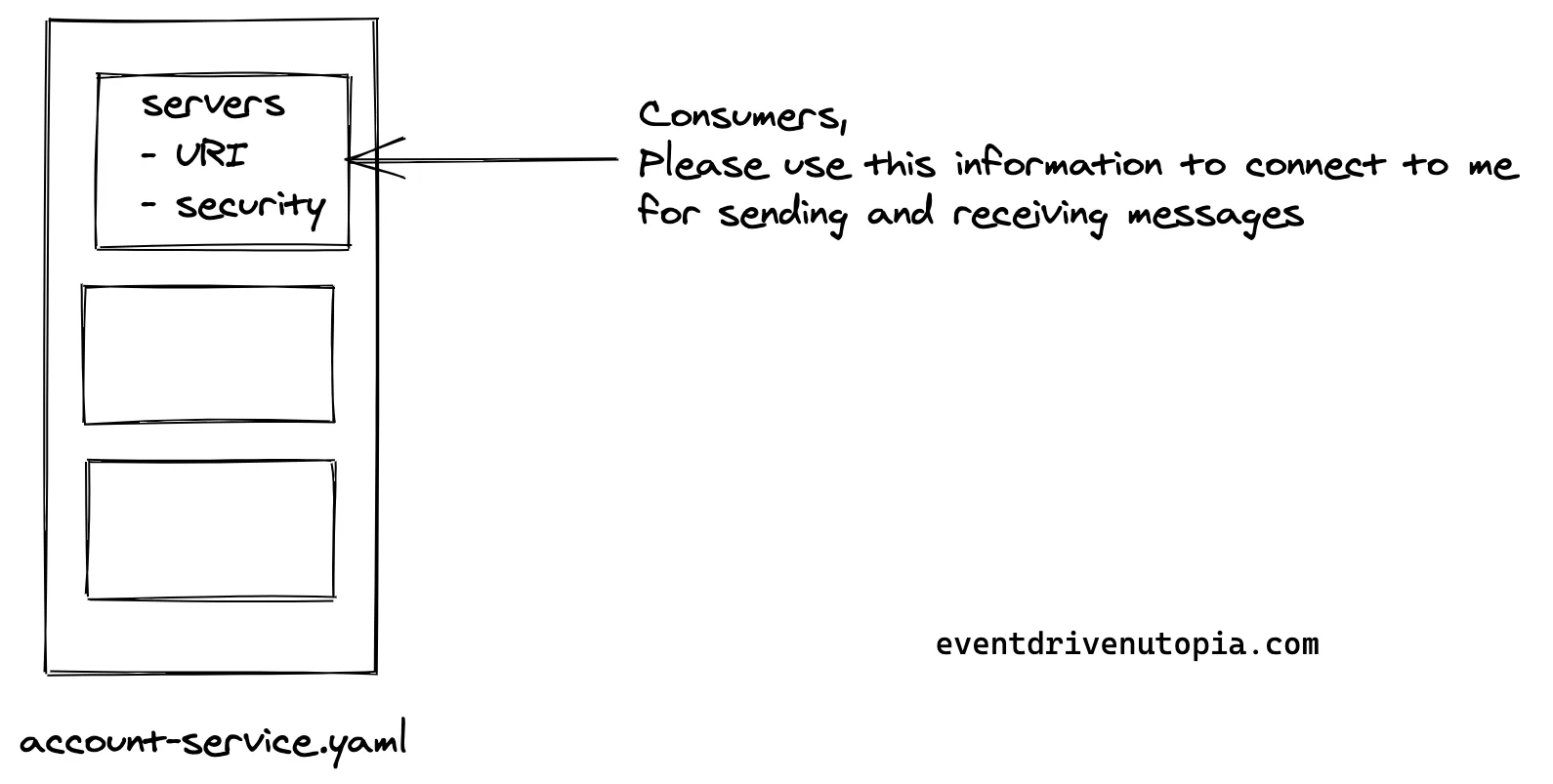

Adding servers

Our solution has been designed around a message broker. Therefore, both Account and Email services MUST specify brokers’ necessary information such as URIs, protocols, and security configurations.

We can use the servers object to define that information for the Account service. In AsyncAPI terms, a server object defines a message broker, a server, or any other kind of computer program capable of sending or receiving data.

Add the following content to the same file. Here, we are using the test MQTT broker available at mosquitto.org. Apart from MQTT, AsyncAPI supports other protocols like AMQP and Kafka.

1servers:

2 production:

3 url: mqtt://test.mosquitto.org

4 protocol: mqtt

5 description: Test MQTT brokerAdding channels, operations, and messages

So far, the Account service consumers know where they should connect to send or receive data. The next step is to define operations on the broker.

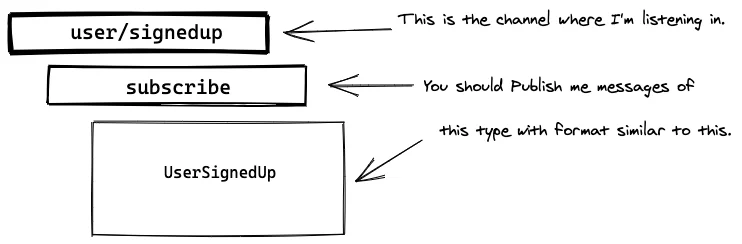

An operation maps to either publish or subscribe method/function in the application. Each operation exchanges one or more messages. Effectively, these messages define different events sent to and received from operations.

Operations are bound to a particular channel in the server, along with the messages they exchange. A channel is an addressable component made available by the server for the organization of messages. Producer applications send messages to channels, and consumer applications consume messages from channels. You can think of channels as the interfaces for external parties to communicate with an application.

There can be many channel instances in a server, allowing messages with different content to be addressed to different channels. A channel is equivalent to topics, routing keys, event types, or paths based on the server implementation.

This relationship is illustrated in the following figure.

In our solution, both services publish and consume events on the same channel.

Add the following section to define a channel called user/signedup.

1channels:

2 user/signedup:

3 subscribe:

4 operationId: emitUserSignUpEvent

5 message:

6 $ref : '#/components/messages/UserSignedUp'The Account service publishes UserSignedUp events to the broker. Hence, it is a publish operation. The operationId specifies the name of the method or function that emits the UserSignedUp event in the generated code.

The above operation uses a reference to specify the format of the message that publishes. We’ll get to the schema definitions shortly.

Defining messages and payload schema

In our solution, both services produce and consume the UserSignedUp event, which has the following format.

1{

2 "firstName" : "John",

3 "lastName" : "Doe",

4 "email" : "aa@bb.cc",

5 "createdAt" : "2021-02-12 09:34:123"

6}The publish operation of the user/signedup channel had a reference to the event payload’s schema. Now we need to define it properly. The schema definitions are done with AsyncAPI schema, which is 100% compatible with JSON Schema Draft 07. Refer to this if you need to explore more on the AsynAPI schemas.

Message schemas, security schemes, and bindings are housed by Components object. All objects defined within the components object must be referenced from properties outside the components object.

After adding the schemas, the final AsyncAPI definition for the Account service file should look like the following.

1asyncapi: 2.0.0

2info:

3 title: Account Service

4 version: '1.0.0'

5 description: |

6 Manages user accounts in the system.

7 license:

8 name: Apache 2.0

9 url: https://www.apache.org/licenses/LICENSE-2.0

10

11servers:

12 production:

13 url: mqtt://test.mosquitto.org

14 protocol: mqtt

15 description: Test MQTT broker

16

17channels:

18 user/signedup:

19 subscribe:

20 operationId: emitUserSignUpEvent

21 message:

22 $ref : '#/components/messages/UserSignedUp'

23

24components:

25 messages:

26 UserSignedUp:

27 name: userSignedUp

28 title: User signed up event

29 summary: Inform about a new user registration in the system

30 contentType: application/json

31 payload:

32 $ref: '#/components/schemas/userSignedUpPayload'

33

34 schemas:

35 userSignedUpPayload:

36 type: object

37 properties:

38 firstName:

39 type: string

40 description: "foo"

41 lastName:

42 type: string

43 description: "bar"

44 email:

45 type: string

46 format: email

47 description: "baz"

48 createdAt:

49 type: string

50 format: date-time Documenting the Email service

Similar to the above, we can create the AsyncAPI specification for the Email service as follows.

1asyncapi: 2.0.0

2info:

3 title: Email Service

4 version: '1.0.0'

5 description: |

6 Sends emails upon certain events

7 license:

8 name: Apache 2.0

9 url: https://www.apache.org/licenses/LICENSE-2.0

10

11servers:

12 production:

13 url: mqtt://test.mosquitto.org

14 protocol: mqtt

15 description: Test MQTT broker

16

17channels:

18 user/signedup:

19 publish:

20 operationId: onUserSignUp

21 message:

22 $ref : '#/components/messages/UserSignedUp'

23

24components:

25 messages:

26 UserSignedUp:

27 name: userSignedUp

28 title: User signed up event

29 summary: Inform about a new user registration in the system

30 contentType: application/json

31 payload:

32 $ref: '#/components/schemas/userSignedUpPayload'

33

34 schemas:

35 userSignedUpPayload:

36 type: object

37 properties:

38 firstName:

39 type: string

40 description: "foo"

41 lastName:

42 type: string

43 description: "bar"

44 email:

45 type: string

46 format: email

47 description: "baz"

48 createdAt:

49 type: string

50 format: date-time

51 description: "foo"Notice that the servers, channels, and payloads are the same. The only difference is in the publish operation, bound to the user/signedup channel. It says that messages published to this channel will be received by this service.

What’s next?

Now we have completed writing AsyncAPI specifications for both Microservices. The next goal is to check-in them into a central location like Git and let both teams collaborate over the design. They can collaboratively edit the spec files to introduce new operations, parameters, versions, etc. Thanks to AsyncAPI, everything can be controlled from a central place, and every change will be visible across the board. I would say this is the pipe dream of an enterprise architect ;)

But our journey doesn’t stop here. The AsyncAPI project brings in a rich set of tools for the betterment of event-driven application building. You can find more information on this here.

Code generators

Application developers can speed up their work by automatically generating scaffoldings by specifying the specification file. This design-first strategy provides boilerplate code for dealing with brokers and marshaling/unmarshalling messages over the wire.

Generators are available for mainstream applications like Java, .NET, Javascript, etc. You can check out this repo for more information.

Validators

Validators validate a given message by comparing it with the specification. That is useful at the runtime for input validations.

Documentation generators

These generators generate human-readable documentation from an AsyncAPI document. Output formats are HTML, Markdown, and React (experimental)

Mocking and testing tools

Tools that take specification documents as input, then publish fake messages to broker destinations for simulation purposes. May also check that publisher messages are compliant with schemas.

Conclusion

Use AsyncAPI specification to document your event-driven systems to maintain consistency, efficiency, and governance across different teams who own each architectural component.

The tooling ecosystem of AsyncAPI helps you speed up application development by automating tedious but necessary tasks such as code generation, documentation generation, validators, etc. Use them whenever you can.

Finally, the AsyncAPI community is growing so fast. Your contribution to the community will be valuable in terms of making better event-driven applications.

I hope you enjoyed this post.

Originally published at https://medium.com/event-driven-utopia

Cover image by silviarita from Pixabay